BLM – To kneel or not to kneel: Are we missing the point?

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour,” Kaepernick said. “To me, this is bigger than football, and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

In 2016, Colin Kaepernick knelt during the playing of the United States national anthem, prior to an NFL (National Football League) game. The world gasped. Some did not know where to look, others pretended it did not happen. Ironically, Kaepernick’s action, at a time when it was not fashionable or acceptable, earned him even more of the racist attacks he was kneeling to protest.

Kaepernick was also called a hero for his stance against racial injustice, inspiring others around the world to make similar dramatic statements. But it is important to go beyond the knee; there are consequences for following one’s conscience. As Kaepernick and others who have walked the revolutionary path know only too well, you make your point, but you pay the price.

In 2021, there is a growing debate over whether athletes should still be kneeling before the start of professional games, whether this action is now past its usefulness, or whether it still has validity as protest action in support of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

It seems to me that such discussions are a distraction, a shifting of focus away from the fact that abuse of athletes of African ancestry has now intensified online. Such debates completely ignore the inequality that still exists for many people of African heritage in their jobs, in finance and in the world of business. And it forgets that in parts of the United States and elsewhere, the African community continues to be impacted disproportionately by the global health crisis that we are battling.

Thus, to kneel or not to kneel. As we try to decide what form of resistance is socially acceptable, are we not missing the point of why people are protesting in the first place?

A global movement against racism

“I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong.” In 1967, Champion Boxer Muhammad Ali refused to go to Vietnam to fight on behalf of the United States. Civil rights activists like Martin Luther King supported his position. Ali’s ideological clarity on the issue was encapsulated when he told an interviewer “…shoot them for what? They never called me n.., they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. … Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

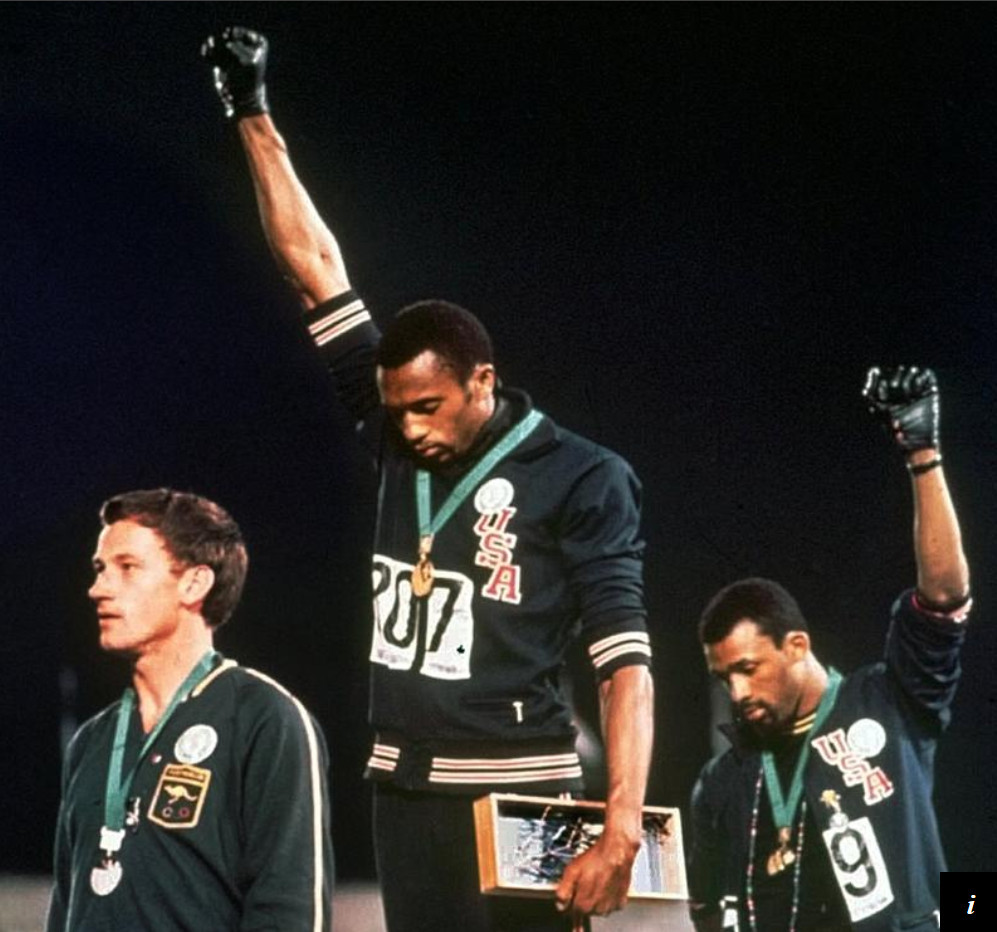

The following year, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists during the playing of the American anthem while standing on the winning podium after the 200 metres race. It was the summer Olympic Games of 1968 in Mexico City and the raised fist had become a powerful symbol of black power, resistance and self-determination. “Smith and Carlos decided to appear on the podium bearing symbols of protest and strength: black-socked feet without shoes to bring attention to Black poverty, beads to protest lynchings, and raised, black-gloved fists to represent their solidarity and support with Black people and oppressed people around the world.”

Smith and Carlos knew the world would listen.

Globally, movements against racial injustice had been building since the 1950s. Anti-colonial movements driven by activists from the Caribbean like CLR James, George Padmore and Claudia Jones mirrored activism on the African continent by leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Sékou Touré.

Across the region, Kamau Brathwaite, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Cheryl Bryon, Lasana Kwesi and others were creating new poetic styles that rejected colonial forms and celebrated the ‘nation language’ of the people. In Trinidad and Tobago (TT), Jamaica and elsewhere, students spearheaded protest action against institutional and systemic racism. In 1968, students of the Sir George Williams University in Canada accused one of their professors of racism. The following year, mass protests by students in TT in solidarity with the Canadian students sparked the Black Power Revolution.

Internationally, there were protests against the apartheid system in South Africa and the support it received from governments who should have known better.

The intensity of civil rights activism diminished after the 1970’s but it did not mean that the issues of police brutality, inequality and institutional racism against people of African heritage disappeared. Indeed, by 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States became more vocal over the inherent disparities of that society. The brutal, public police killing of George Floyd in May 2020 opened a portal of protest that spread from the streets of Minneapolis across the world. The acts of kneeling and raising of fists moved beyond their connection with the playing of the national anthem of the United States. The actions of the Black Lives Matter movement resonated with people across the world who acknowledged that deep-rooted racism was reflected in virtually every aspect of life from politics to education and public symbols such as statues.

Despite the impact of the movement, sporting bodies have sought to curb this show of solidarity with BLM.

“Any kind of boycott for whatever reason is against the mission of the Olympic Games and I ask them to respect the political neutrality of the Olympic Games by not using them as a stage for their political purposes.”

Thomas Bach IOC President, January 2020

Confusingly, in 2020 the International Olympic Committee banned taking a knee or raising a fist at the Olympic Games planned for Tokyo. Is that not the whole point of protest, to disrupt the status quo? Suppose athletes decided to lie down, sit, or take other action during the playing of national anthems, would they all have been banned? As a journalist wondered out loud when Muhammad Ali refused to go to Vietnam, what would happen if 100,000 young men decided to take the same action?

Michael Holding, Caribbean cricketing legend has been publicly emotional about his own encounters with racism. Reacting to the banning of kneeling by the England team, Holding stated, “I don’t care about the politics behind Black Lives Matter. I care about those three words: Black Lives Matter. It is time for the world to accept that black lives matter and move towards that agreement and realisation.”

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrffW5au8lA

What is it about a national anthem?

National anthems are aspirational.

Often composed against the backdrop of struggles for independence and other freedoms, national anthems seek to inspire those in the present, address past errors and lay out a prescription for the future. ‘Where every creed and race find an equal place’, ‘No tyrants here linger, despots must flee this tranquil haven of democracy’, ‘Black star of hope and honour, to all who thirst for liberty’, ‘The land of the free and the home of the brave.’

Anthems represent the duty and commitment of a nation’s military and are played at all official political, sporting and cultural events. As symbols of diplomacy, it is imperative to play a country’s anthem correctly and according to the appropriate order of precedence. In TT, there are stories of people being arrested for talking during the playing of the anthem.

National anthems like country flags and national watchwords are serious stuff.

It also makes sense that in order to make a statement, protesters would seek to disrupt the sanctity of the playing of a national anthem. Smith and Carlos who raised their fists on the podium in Mexico understood this. “It was a cry for freedom and for human rights… We had to be seen because we couldn’t be heard.”

To kneel or not to kneel? Yes, we are missing the point.

There are consequences to taking a revolutionary position.

In TT, Eintou Springer, Khafra Kambon, Clive Nunez and others seminally involved in the Black Power movement are still not quite accepted by society. Smith and Carlos “received hate mail and death threats” and their personal relationships and job prospects suffered. They were banned from the Olympics for life. Muhammad Ali was banned from boxing for three years. Almost fifty years later, Colin Kaepernick too paid a price. Ostracised from the game of football for four years, only in 2020 was he able to go back to the sport he loves.

There are consequences to being a hero.

But there are also rewards. Kaepernick spent his time away from the game supporting community-based organisations and charities dedicated to fighting institutional racism and empowering the people who rely on their interventions. The BLM is forcing institutional changes within the police force and President Biden has been making positive statements about his intentions to address inequities in areas such as education.

Meaningful change is still a distance away though. The 400-year-long period of enslavement created systems of wealth acquisition and distribution for the western world that were founded on inequity. We cannot forget about it, because these systems are still with us today.

So, to kneel or not to kneel is not the issue. Whether citizens, kneel, stand, sit or raise their fist, the ultimate goal is justice. And that is what we should be debating. That is the point.

Ase. So be it.

Obeah: The healing magic of African spirituality

Mama Yemoja Fierce beauty lapping gently at my feet In generational ritual I bow before yo…